What do you think XR's analog joystick is?

XR's game design affordances, the importance of the N64's analog joystick, and a question for you

This article is written exclusively for educational purposes, I do not own any of the media shown or referenced. This is a written form of a talk I’ve given at the XR Guild, as well as NYAR

Why do we keep bringing non-XR games into XR?

A brief history of what VR tie-in games came to be

During VR’s gaming infancy we saw an explosion of shoe-in VR titles based off of other existing gaming properties. There was a blip in time where studios created unique VR spin-offs, but these were few and far between. Batman Arkham VR was one of the first to build a compelling VR tack-on experience. Releasing just after Batman Arkham Knight, the hour-long experience gives us access to the Bat-Cave, a few sections of detective sleuthing using evidence to construct holograms, and a short story involving the characters from the game.

Unfortunately this was one of the few child-VR titles to properly come out of this era, and its level of quality and polish wasn’t the norm. We quickly began to see VR-ports of non-VR titles spring up like wildflowers. Many would simply throw in a control scheme compatible with basic VR control schemes, replace their character controller, and call it a day.

The worst culprits of this are most of the AAA projects. It was attempted a few times, with some being more successful than others. The most notably successful of these was The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim VR, which exchanged the normal player with a VR rig and ensured the game was VR compatible. If it proved anything, it was that with enough time, energy, money, and experience, a team could successfully bring a non-VR title to VR.

Outside of Skyrim VR there are no other titles which prove this to me. One of the biggest flops of this sub-genre has to be Borderlands 2 VR, which took lukewarm steps to ensure the game’s VR compatibility. While there are some neat elements such as manual reloading of every generated weapon in the game, it ultimately fails to capture what makes Borderlands 2 so enjoyable on every other platform, because it wasn’t made for this one.

What makes an XR experience enjoyable?

When I think of XR games very few come to mind that I truly enjoyed, but the few that do left a crater of an impact on the industry. The three most influential to me are SUPERHOT VR, Beat Saber, and Pokémon GO.

More often than not when I find myself taking a more critical perspective on a game, it’s due to the fact that the game fails at “the thing you are constantly doing.” You see it all the time in the industry, a title releases promising an exciting specific experience and then falls flat because the core just isn’t there. Sometimes it’s a strategy game that focuses too much on its romance system, neglecting the strategy and combat which players bought the game for. Other times a shooter forgets it’s a shooter, and decides to pile on mechanics instead of focusing on its core gameplay.

The three games I’ve mentioned don’t just hone in on their core, they build on their methods of interaction without abandoning their specific modes of character. Each of them takes advantage of XR’s unique aspects to deliver an experience you can’t build outside of XR, as opposed to the tie-in projects mentioned above which deliver a non-XR experience through XR.

Beat Saber

You’re playing with lightsabers. I mean - come on. Not much more has to be said.

Beat Saber’s basic idea is playing with laser swords to destroy boxes to a beat. It’s clear, cut, and direct. And it can only be done in VR. Here, the main affordance of note is the relationship between the VR controllers and the movement of the player’s body. Before we’re managed to create experiences in which moving our body allows for more interesting play. The Nintendo Wii is more notable for this, creating widespread interest and acceptance of motion controls in the world of modern gaming. Wii Sports (2006) was the first experience that proved motion controls could be done well with constraints. Microsoft attempted to take this a step further with Kinect, which ultimately did not mesh well with audience, and ended up being a moderate success in the industry. Sony invested in the PlayStation Move, which was more similar to the Wii remote than anything else.

Ironically we can point to these and identify the same affordances which VR provides the player through motion. It is the execution of perspective and the increased accuracy of tracking which solves the majority of issues players had. This relationship allows for games such as Beat Saber to come into being.

There’s a sense of familiarity when you player Beat Saber for the first time. I think almost everyone I know has played with a toy lightsaber before, and dreamed about the adventures they might go on if they were suddenly whisked away to a far off galaxy. The sensation alone of swinging your arm and slashing something in half is already, on its own, so wildly satisfying. Doing it to your favorite songs is even more intense.

Another aspect which accompanied accurate motion tracking which I rarely see mentioned was decreased tracking latency. It is this lowering of input-lag which made the rhythm aspect of Beat Saber possible. Many games have attempted similar motion-to-rhythm relationships before. Just Dance overcomes the latency of many consoles by turning this into a one-way relationship. They judge your performance by how well you match the motion of the figure on the screen, not by how well timed the motion is. Because the game knows what the player is going to do, it can compare delayed motions and analyze their accuracy. This same concept is applied in many other games in reverse, where the game knows what the player is going to do next and plays a predictive animation. Assassin’s Creed is a good example. When the player is running towards a wall, the game knows they want to climb it, so it plays the animation of Ezio approaching and clambering up the wall.

Rhythm games ask the opposite of the player. When a string of notes flows down the track in Guitar Hero the player begins to think about the placement of their fingers and the timing of their strum bar. They plan out their motions and understand when to play the notes. The opposite of Assassin’s Creed predicting what the player wants, it asks the player to predict what the game wants.

Beat Saber didn’t have to grapple with the design issues Just Dance faced because the method of interaction was improved. VR requires extremely low input latency to avoid user discomfort. It allowed them to create one of the few successful motion-rhythm games ever. Where Just Dance could compare what the player was supposed to moments before, and Assassin’s Creed could accurately predict what the player wanted to playback a motion on the screen, Beat Saber works in reverse. It presents the player with a required set of motions, just like how Guitar Hero asks the player to predict when and how to play notes. The player must combine the aspects of motion of Just Dance and the elements of accuracy in Guitar Hero in order to accurately predict and interpret the motions to strike notes in Beat Saber.

It is the affordance of accurate low latency motion which makes this possible, and is one of the few key components which VR is able to leverage so eloquently.

SUPERHOT

Riding off of the core of Beat Saber we are able to quickly transition into a similar motion-based game. SUPERHOT’s main idea is: Time only moves when you do. It was first prototyped and created for PC and consoles, which is ironic, because so few VR games feel as made-for-VR as SUPERHOT does. In the PC version of the game, movement is judged as any keyboard or mouse input which the player makes. If they stand perfectly still, so does time. But VR tracks the movement of our body - have you ever tried to stay perfectly still?

Playing directly into the idea of full body motion is what makes this game just so fun. Being able to tap bullets in midair, throw objects at enemies, and dodge attacks in (what feels like) a controlled real time experience, makes you feel like Neo from The Matrix. It’s this specific relationship which makes this first person shooter unique.

Pokémon Go

Pokémon Go’s core idea was something the franchise had toyed with since its original inception - Pokémon in the real world. Even from the original entry, users could swap monsters with one another on the playground. You could battle your friends in the world together. As the franchise evolved we saw more and more aspects of this concept introduced, most notably the Pokéwalker, a step counter which allowed you to train your team by walking around in real life, and the use of StreetPass which rewarded players for passing another 3DS user in the real world.

The concept of “Pokémon in the real world” was directly reinforced by one of the core affordances of XR: Direct interaction of the digital and physics space. Designers were able to place monsters in the real world to be caught. Elements of the other games which attempted this concept were quickly bought to Pokémon Go. Trading and Battling were introduced as the game became more popular, but StreetPass elements were added almost immediately. Poké-stops allow users to collect resources and apply bonuses for others, attracting Pokémon and providing additional resources. In this case it was the affordance of real-world interaction that created a new relationship between the player, technology, and the world.

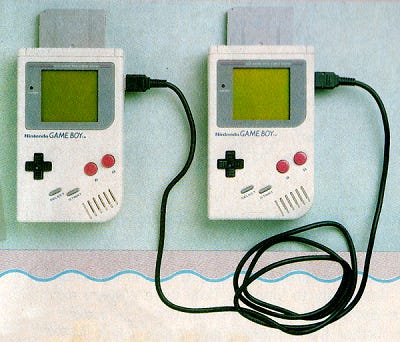

As mentioned before, that’s not where “Pokémon in the real world” started. Ever since the earliest days of the first game on the original GameBoy released in 1996. The idea fits right into the franchising, as the core premise of the TV show focused heavily on the relationships between Pokémon and their trainers. Every kid who watched the show wanted a Pokémon of their own to be their best friend, not only because they could shoot fire from their mouths, but because of the close partnership to be shared.

In many ways it’s a similar emotion to the relationship between children and their pets, except that Pokémon are conscious and can understand English. It’s something which kids found familiar and could understand. Nintendo definitely understood this, which is more than likely why they implemented both Trading and Battling into the very first game.

The Link Cable was used by more than thirty games on the console to enable multiplayer, but it was leveraged by Pokémon: Red, Blue, and Yellow to incorporate battling and trading. This quickly made these games far more than just siloed experiences. You could find, catch, and train your own team of Pokémon, then bring them to a friend’s house and have a battle. It made you feel as if you were actually discovering them in the real world. This was especially true if you brought your Pokémon team to tournaments.

As Nintendo consoles evolved to have local wireless communication, handheld consoles could talk to one another without the need for the Link Cable. This allowed for a few other methods of functionality which incorporated the real world. One of the more interesting ones was StreetPass, in which you could wirelessly and automatically communicate with other 3DS consoles you passed by on the street.

We saw other evolutions of this concept, such as a physical Pokéwalker which you clipped to your belt or backpack, which tracked your steps in the real world allowing you to train your Pokémon as you walked around.

Without exaggeration, all of these ideas were translated into the context of XR through Pokémon Go. Battling other players in your vicinity was introduced through gyms at launch and direct challenges later on. Trading can be done by walking up to another player and asking them to trade. Your steps are counted and used to level up your team. In order to progress you must spend time in the world, walking around and collecting Pokémon.

What’s the point of an affordance?

With all of this in mind, I’d like to pose a question. I’ll preface this by saying that I don’t think it has a specific answer, nor do I think it has one single valid answer.

Consider the design of the N64 controller for a moment. While it may not be ergonomically sound, and appears to require three hands to operate, it features a component which redefined controllers as we know them. Right in the center it has an analog joystick.

While this wasn’t the first joystick we had seen, it was the first of its kind to translate an analog input to a digital one with a high level of accuracy. Rather than a simple series of binary directional inputs, it was able to sense slight changes in the stick. It was this design which allowed for new relationships between the player’s input and the feedback from the game to take form.

This was so popular, in fact, that every controller after it began to include it. Even the Playstation 1’s controller, which originally shipped without an analog stick, had a revision released after the success of the N64’s controller, so much so that the two companies got into a legal battle over whether or not they were stealing features from one another.

To this day it is difficult to think of a controller which does not feature an analog stick in one form or another. Even the Wii remote which did not have one built on the controller itself shipped with the Nunchuck attachment which one could plug in to receive analog functionality.

With each new method of input, new methods of play were created. When considering XR game design, we must consider what new design affordances each feature brings. Rather than continuing to build game concepts that we’ve already established for other methods of play, we need to begin our process with ideas, and work towards designs which leverage these control schemes more directly.

Pokémon Go used all of the tools available in XR to build the best “Pokémon in the real world” experience that they could. You don’t move through the game with a touch-screen joystick, you do so by walking. The game is built from the ground up with XR in mind.

Which brings me to the question I’d like to pose to all of you:

As I had said before - there is more than likely not one answer to this. In fact I believe there is not one “analog joystick” for this generation of gaming. Remember that the analog joystick is a representation of something more: a new method of interaction that caused us to change our approach to designing experiences.

In XR this may already be found, or we may never find it. There could just be one, or there may be hundreds. Ultimately this is a very open ended question, but it’s one I’ve been pondering for quite some time.

We’re currently in a rapidly developing XR space, with new products quickly finding their way to market all the time. And so, I’m curious to hear what you think. Have we been sitting on XR’s analog joystick this entire time? Are we in the process of finding it? Are there other experiences which jump to mind when considering unique or new forms of interaction?

I’d love to hear from you. Thanks for reading.